Urnings, in Ireland and Illinois

- Tom Hulme

- Jun 9, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 2, 2025

Wheaton College, sometimes dubbed “the Harvard of Evangelical Schools,” lies about twenty-five miles west of Chicago. In early November 2022, just a few days before I presented a paper at NACBS about queer Irish sailors, I made the fifty-minute journey by trundling commuter train from downtown Chicago to visit the college’s Marion E. Wade Center. Serenely housed in a bucolic English-style cottage, the Center holds the personal archives of several notable British authors and lay theologians, from G.K. Chesterton to Dorothy L. Sayers.

Suburban Illinois and a devout Christian college might seem an unlikely place to start a story about researching the queer history of Northern Ireland… but God moves in mysterious ways. So, you may ask yourself, “Well, how did I get here?”

I moved to Northern Ireland from London in 2016 to take a lecturing post at Queen’s University Belfast. After finishing my first book soon after – a non-queer comparative study of British and American culture in the interwar era – I was searching for a new project. I had “come out of the closet” about a decade before, while a student at the University of Leicester, and now seemed as good a time as any to turn my personal investment in gay history into a professional one. I started by emailing the most prominent gay rights activist in my new home, Jeff Dudgeon, for advice. His reply was generous but admitted, “Early 20th century gay history in Belfast will be a bit of a task.”

I learned that there are exceptional archival collections for the gay rights movement that gathered steam in Northern Ireland after the formation of a local Gay Liberation Society in 1972, and much about religious-inspired homophobia, so vividly captured by the late 1970s campaign of the Reverend Ian Paisley to “Save Ulster from Sodomy.” But the era before remained shrouded in mystery. The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland had a legal archive that began to tell me something about where men briefly met and what they did with each other sexually, but I desperately hoped to find more emotionally intimate material too.

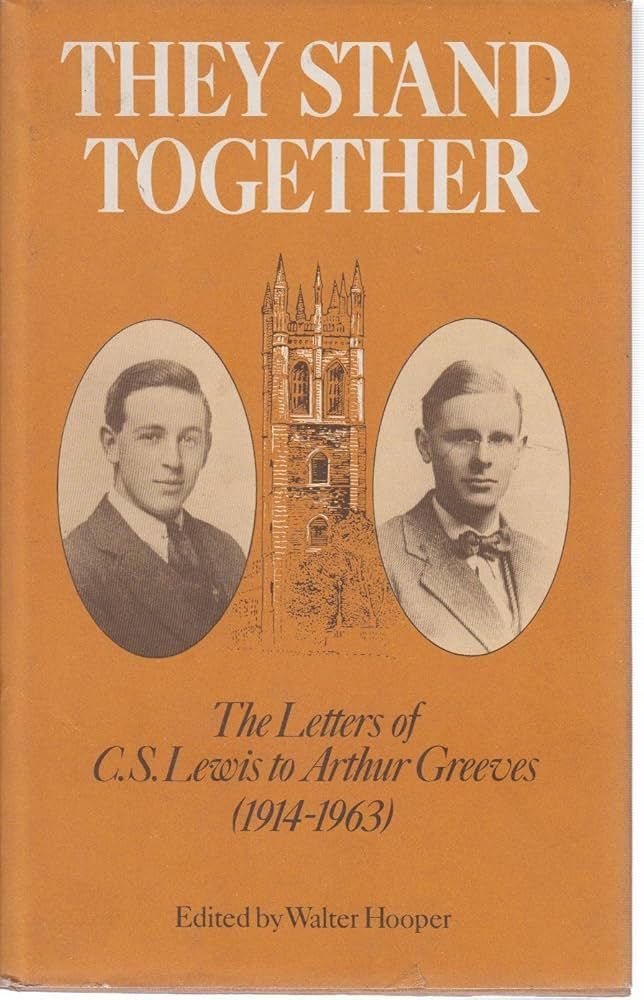

Fortuitously, a colleague at Queen’s–an expert in religious history–suggested that I read the collected letters of the famous Christian novelist C.S. Lewis and his closest childhood friend Arthur Greeves. The two men grew up in Strandtown, which by the early twentieth century had become a salubrious suburb for the wealthy elites and industrialists of booming Belfast. Most of the letters from Greeves have been lost or destroyed, but Lewis tended to repeat back the conversation points of his less loquacious friend. My interest was piqued early by their discussions of wet dreams, or “going north” as they euphemistically termed it, and even more by Lewis’s fetishistic daydreams about whipping women (including Greeves’ sister!). When, in early 1917, Lewis asked Greeves about his thoughts after reading Edward Carpenter’s The Intermediate Sex, I knew it was worth digging more.

And so, I ended up in Wheaton.

The Marion E. Wade Center’s extensive C.S. Lewis collection originated from communication between the author and Clyde S. Kilby, an English professor at Wheaton College, in the 1950s. At some point it grew to include two diaries written by Arthur Greeves. Lewis scholars have been intrigued by the author’s close relationship with Greeves but unsurprisingly less so in the everyday life of this quiet and otherwise unknown man. For this reason, the diaries have only briefly been used, and never as a source for the queer history of Northern Ireland.

The first diary covers Greeves’ daily life in Belfast in 1917 and 1918, when he was in his early twenties, and is largely in scribbly notation form. Though tricky to parse, it tells a journey of personal discovery, from painful unrequited love for his dear friend Lewis to attempts to court other young men he felt were struggling with the same desires. After being introduced to the work of Carpenter through a sympathetic and well-read cousin, Greeves buries himself in the even rarer writings of sexologists like John Addington Symonds and Havelock Ellis, as well as suggestive historical texts, such as the work of the French Renaissance philosopher Michel de Montaigne. One young man in Belfast now came to understand himself as an “Urning.”

The second diary, written mostly while he was living in England and visiting Oxford in the summer of 1922, is in long form and different in tenor. Now less certain about the possibilities of living a homosexual life, no doubt troubled by his own religious guilt, Greeves describes his delight in being introduced by doctor friends to the curative promise of psychoanalysis. When he travels home to Belfast, he learns that fellow traveller friends were wary of the ideas of Freud but essentially hoping to control their desires in much the same way. The diary ends suddenly and not with successful sublimation, but rather visions of ravishing male youths.

The theorist Jack Halberstam has written influentially about a “scavenger methodology” for queer studies: the combining of disparate methods and disciplines that may seem to be theoretically oppositional. But the term also hints at how many queer historians often have only scraps of evidence to work with. For those who study the pre-gay liberation era especially, there is rarely one obvious archive waiting to be written up into a compelling history of a subaltern community scene. Material instead must be gathered from a range of sometimes unlikely places. Alongside Greeves’ diary in Wheaton, Illinois, in my work I have drawn on other scraps, from oral histories in New York’s Public Library to the registry office of New Zealand.

Like the men I write about, evidence of lives cannot easily be restrained by the borders of the nation state, nor the criminalizing lens of the legal archive. It is only by searching far and wide, and stitching many queer fragments back together, that we can create new and often hopeful tapestries of local queer life.

Tom Hulme is a Reader in Modern British History at Queen’s University Belfast, where he leads the AHRC-funded project “Queer Northern Ireland: Sexuality before Liberation.” He is the author of Belfastmen: An Intimate History of Life before Gay Liberation (Cornell University Press, forthcoming 2026), and related articles in Irish Historical Studies (2021), the History of the Family (2024), and Journal of the History of Sexuality (forthcoming 2025).

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the original author/s and do not necessarily represent the views of the North American Conference on British Studies. The NACBS welcomes civil and productive discussion in the comments below. Our blog represents a collegial and conversational forum, and the tone for all comments should align with this environment. Insulting or mean comments will not be tolerated and NACBS reserves the right to delete these remarks and revoke the commenter’s site membership.

Comments